By Alexander O. Smith, Kamakura

By Alexander O. Smith, Kamakura

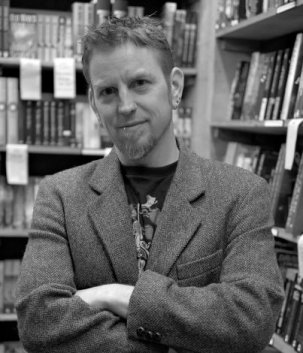

The recent death of Shigeru Mizuki (1922-2015, eulogized here in The New Yorker and here in The Comics Journal) brought deserved attention to this artist’s remarkable life, and to his manga about Japanese folklore and history. His works often appeal to children and young adults. A major translator of Mizuki’s manga, Zack Davisson, agreed to an interview here about his career and approach. His latest Mizuki translation, The Birth of Kitaro, is forthcoming in May 2016.

Hello Zack, many thanks for agreeing to do this interview for us. To start us off, could you give us a little bit of your background, and tell us what you’re currently working on?

I’m a translator and writer who specializes in Japanese folklore and yokai. I wrote my MA thesis on yurei, which I turned into my book Yurei: The Japanese Ghost. I currently translate several manga series, and am working on a new seven-volume collection of Shigeru Mizuki’s classic yokai comic Kitaro. The Birth of Kitaro, due out in May, is the first volume in this collection.

Literary translators often have two stories to tell about how they got where they are: the story of their growth as a translator, and the story of their growth as a writer. How did you develop your skills on both sides of the Pacific?

Growing up in Spokane, WA, writing was something I was always good at. Like some kids were good at sports, or math, words held no mystery for me. But I never thought about writing seriously—I wanted to be an artist. It took me four years of art school to come to terms with the fact that I would never be anything other than a middling talent. Certainly not able to compete on a professional level. But I still wanted to do something creative, and living in Japan in my thirties sparked the idea of doing freelance writing. I started out small, writing for my local JET newsletter. When that was well received, I moved up to paid magazine gigs for Japanzine and Kansai Time-Out. Then when I was doing my master’s degree with the University of Sheffield, at their Hiroshima branch, I got into the idea of turning my thesis into a book. A book I ended up rewriting completely about 5-6 times.

Translating was an extension of all this. I did translation assignments for my MA, and I found I liked doing them. We translated a broad spectrum of works, from short story science fiction to news articles to blog posts, getting a feel for how to change styles to suit the source. My first translations were terrible; clunky and laboriously faithful to the source material. But I started to feel my way around in how to put the words on the page.

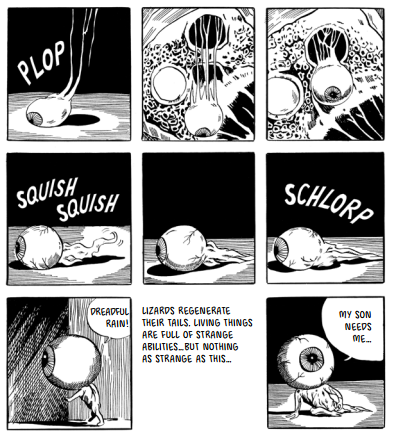

And then manga translation was just pure love of comics. I’ve been a comic fan for as long as I can remember, including owning a comic book store with the massive collection that that entails. It was something I wanted to do, so I learned how to do it. I also took an already translated manga—Dr. Slump—and I went through it volume by volume doing my own translation, then compared it to the published work to see what they were doing and how they did it. [Translated by our interviewer, Alex! –ed] It was excellent practice and something I recommend to anyone who wants to translate manga. Page from The Birth of Kitaro courtesy Zack Davisson

And then manga translation was just pure love of comics. I’ve been a comic fan for as long as I can remember, including owning a comic book store with the massive collection that that entails. It was something I wanted to do, so I learned how to do it. I also took an already translated manga—Dr. Slump—and I went through it volume by volume doing my own translation, then compared it to the published work to see what they were doing and how they did it. [Translated by our interviewer, Alex! –ed] It was excellent practice and something I recommend to anyone who wants to translate manga. Page from The Birth of Kitaro courtesy Zack Davisson

I subscribe to the 10,000 hours theory, that you need to endure a period of hard ass, grindstone practice before you become fluent in a skill. The ones who don’t make it through that particular crucible never reach the professional level.

You’ve written about supernatural Japan in Yurei: The Japanese Ghost and on your website, hyakumonogatari.com, and your translations of Mizuki Shigeru’s Kitaro comics are filled with yokai. What drew you to this genre?

Ghosts and the supernatural are something that I have always found interesting. As a kid in the 70s I used to watch this show called In Search Of, and I pored over books like Time Life’s The Enchanted World and a great gnome book that I can’t remember the title of. I liked the concept of a mysterious world of folklore. I lived in Scotland for a bit and toured around, going to the Brig o’ Doon and the fairy bridge on the Isle of Skye. I even had a Loch Ness Monster sighting.

Going to Japan was like hitting the jackpot. The country was alive with folklore and magic and mystery and lived with it in a day-to-day way that I hadn’t imagined. I was fascinated by everything, and wanted to decipher every character on every temple wall or shopkeeper’s shelf and figure out what it all meant. And when I discovered Shigeru Mizuki—that was life-changing. His characters and work were everywhere, but I had never heard of him. And the more I plunged into his world, the more I wanted to know, both about the yokai world and about Mizuki himself.

There was this whole wonderful, hidden world locked tightly in a box of which language was the key. I made it my mission to take up the torch from Lafcadio Hearn, and through translation and writing make more of this exquisite awesomeness available to an English-speaking audience.

One challenge YA authors whose work spans multiple cultures grapple with is how to introduce concepts from a culture that may be unfamiliar to their readership in a way that will inform and develop a sense of place without leaving their audience behind. You’ve chosen to leave words like yurei and yokai in Japanese. What informs your choices about what to leave “unlocalized,” and what strategies have you used to introduce these terms?

One challenge YA authors whose work spans multiple cultures grapple with is how to introduce concepts from a culture that may be unfamiliar to their readership in a way that will inform and develop a sense of place without leaving their audience behind. You’ve chosen to leave words like yurei and yokai in Japanese. What informs your choices about what to leave “unlocalized,” and what strategies have you used to introduce these terms?

I had some back-and-forth about that with my editors, but I felt strongly about keeping those words in Japanese. I think this is also part of the art of translation—knowing when to not translate a word. I read older translations from the 1800s where samurai was translated as knights and yokai as faeries, and the translations are horribly dated. They don’t read well because they are overly localized to resemble Western fairy tales. I’ve read similar translations of Arabian Nights where they did their best to scrub the “Arabian” part, going so far as to introduce Christian parallels.

That said, there has to be a reason for leaving a word in the native language. You are essentially introducing a new word into the English language. But that reason has to be beyond exoticism. Or laziness . . . like you said, it is that balance of sense of place and readability.

For me, it was that the precedent had been set centuries ago for world folklore—you don’t translate monster names. Leprechauns are leprechauns. Banshee are banshee. Penanggalan are penanggalan. These are very specific, culturally bound terms that are not possible to translate. It’s better to educate.

I used a few strategies to introduce these terms, mostly my beloved em dash. You can drop that in to give a quick clue. “We’re surround by yokai—monsters everywhere!!!” I’m not a huge fan of Translator’s Notes. If possible I want to give clues in the main text so readers don’t have to flip back and forth. I also write Yokai Files for every volume of Kitaro. The Yokai Files highlight all the yokai in each volume, and help readers get acclimatized to the names. But I think of those as “bonus features,” instead of required for the main text.

At the end of the day, you have to trust readers, even young ones. I ultimately made the argument that if kids could handle Pokémon and Pikachu, then they wouldn’t stumble over Nurikabe and Nezumi Otoko.

Your work spans literary translations from classical Japanese, such as The Secret Biwa Music that Caused the Yurei to Lament, to translations of much more modern material. How does the age and style of the source material influence your creation of a style or authorial “voice” in the translation?

Your work spans literary translations from classical Japanese, such as The Secret Biwa Music that Caused the Yurei to Lament, to translations of much more modern material. How does the age and style of the source material influence your creation of a style or authorial “voice” in the translation?

That’s something very important to me. I translate works from different eras because I enjoy reading from different eras. I love Charles Dickens and Nathanial Hawthorne. And when you translate works from those eras they should reflect the literary style of the times. The prose was more patient. The vocabulary was more verbose.

Translating from different eras flexes different literary muscles as well, which I enjoy. Although I can’t overdo it. I spent a couple months doing some very early Edo translations, and it made my brain hurt. I needed to do some modern manga as a break after that!

Tell me about what’s it’s been like working on Mizuki Shigeru’s comics. His output spans a wide range of genres and readership ages. How aware are you of your target audience’s age when you translate, and what do you change, if anything, when translating for younger readers?

Absolutely I am aware. I didn’t translate Showa: A History of Japan with the same vocabulary that I used to translate Kitaro—nor did Mizuki write them at the same level. That’s one of the things I love about Mizuki, is that he offers such a broad range of depth and styles in his work. I did a translation of some of his art commentary, and people were amazed that the same person who wrote Kitaro was capable of such poetic language. Working with Drawn & Quarterly is great in that they want to present a complete picture of Mizuki as an artist, and have allowed me to work on some things that I never thought would get English translations.

With Kitaro, the goal is “kid friendly.” That means I follow the basic reading level rules, use simpler vocabulary and shorten the sentences. But I don’t dumb down the concepts, and every now and then I throw in a word that kids might have to look up. I think that’s important. When I was a young reader, I liked books that challenged my vocabulary. I want to pass on that feeling of accomplishment.

You collaborated with artist Mark Morse on an original comic, Narrow Road. Where did the idea for that project originate? How did you divide storytelling duties between yourself as the writer and Mark as the artist?

You collaborated with artist Mark Morse on an original comic, Narrow Road. Where did the idea for that project originate? How did you divide storytelling duties between yourself as the writer and Mark as the artist?

I think many translators eventually have the itch to do something of their own. My collaboration with Mark was kind of dipping my toes in those waters. I had seen him on Twitter and was really taken with his art. I reached out to him, and he was open to collaboration. We had similar ideas, of doing something with Buddhist traveler’s tales in a non-didactic way. So we did a test story and found that we enjoyed working together.

With comics it is hard to say how the storytelling duties are split. I give him a full script, which includes panel-by-panel breakdowns and art suggestions, but he has plenty of room to improvise. Sometimes I will insist on things, especially if they affect the pacing of the story, or the timing of a gag. But his sense is great and he always improves on the initial ideas. I have only had him go back and redraw something once, but that was because I had a new idea once the art was done.

We hope to keep going. The reception has been good, and doing the work is rewarding. I just sent him the next script yesterday. We’ll see where the Narrow Road takes us!

Have you collaborated with other artists/editors/translators/writers? What different arrangements have you tried, and how did they work out? Anything to recommend to YA authors or translators contemplating collaborative projects?

My experience with editors has been 100 percent positive. I don’t know if that is just luck, but it has been good experiences all around. My personal goal as a translator is to get as many of my words on the page as possible. I generally get everything up there, with only a word or two changed for a 500-page comic. But even then I go over the finished version to see what changes were made and try to learn from that.

A new collaboration is always tricky, as you have to sort of feel each other out. I am starting a new project with an Italian artist, as well as doing some work with different editors at a new company, so that will be interesting.

If possible, it is nice to establish a relationship over time. When I first started with Drawn & Quarterly, there was more back-and-forth with editorial, especially on how to present Mizuki’s language. But having worked together for years now we are in synchronicity, and have developed a wonderful level of trust. You’ll see the fruits of that in the latest Kitaro, where I was able to add quite a bit of additional content to the main text. It’s a lot of fun!

Many YA authors/translators teach, edit, or write outside their main genre. Is translation/writing your full-time occupation?

Many YA authors/translators teach, edit, or write outside their main genre. Is translation/writing your full-time occupation?

Unfortunately, writing and translation does not pay enough to serve as my sole occupation. I have a full-time job on top of my translation/writing work: writing and editing for a big company. I try to keep my day job private, although everyone at my office knows about my “other life.” It’s a tough balance—I essentially have two full time jobs, and that means sacrifice.

When I started tackling Mizuki’s manga Showa: A History of Japan, I knew that I would have to make changes to my life if I wanted to be successful. So I cut out a lot of things that people do for fun in favor of long stretches of isolation propped over a keyboard with a tankobon (paperback) propped open. Sometimes I wish I could just chill out and play a video game or something, but I don’t have the time. I haven’t played a video game since about 2008.

On the plus side, my regular job gives me the luxury of only taking on freelance work that I am personally interested in. I don’t have to do crap work just to pay the bills. And each manga I translate or book I write is an individually hand-crafted work of love.

Some YA authors/translators struggle with self-promotion. You’ve been a presence at many conventions, such as Comicon and Sakuracon. How important has it been to you to attend cons, either as a presenter or an attendee? Any other promotional activities that you would recommend to others?

I am a huge extrovert, so self-promotion is part of my package. I tell publishers that when they hire me, they not only get the translation but they get my enthusiasm as well. To me that is a key part of the work, especially conventions. I just did Emerald City Comic Con, and put over a hundred copies of Mizuki’s works into hands of people who had never heard of him before. Those are people who would have never tried his work if I hadn’t been there.

I am a huge extrovert, so self-promotion is part of my package. I tell publishers that when they hire me, they not only get the translation but they get my enthusiasm as well. To me that is a key part of the work, especially conventions. I just did Emerald City Comic Con, and put over a hundred copies of Mizuki’s works into hands of people who had never heard of him before. Those are people who would have never tried his work if I hadn’t been there.

I also do presentations, which is something I personally enjoy. I am trained as a public speaker and taught for years, so standing up in front of an audience is something I am comfortable with. I also publish articles on various sites, like my recent Confessions of a Manga Translator article for The Comics Journal, which got a surprising amount of attention. Each article or presentation serves dual function as an advertisement. Getting your name out there is important to generating sales, as well as getting new work opportunities. Networking is essential. I just today signed a new contract for a translation that came directly from a conversation at Emerald City Comic Con.

Recently I have been trying to build my Twitter network of translators. After the “Confessions of a Manga Translator” article, I have been hearing from fellow professionals and it has been great. Twitter is a great tool for making connections with people that you are geographically separated from.

Did you face any early challenges to finding success in your translation and writing?

Getting someone to take a chance on that first work is the greatest challenge. Until you have your first published work—until you make that move to professional—you are a gamble for publishers. They don’t know if you can meet deadlines. They don’t know the quality of work you can deliver. They don’t know if you will make their jobs easier or more difficult.

I told Drawn & Quarterly publisher Chris Oliveros that he changed my life by giving me my first job translating Showa: A History of Japan. Everything has built on that initial chance he gave me.

You work on Japanese material, but live in the US. What challenges and advantages does your choice of location present, both in “keeping in touch” with both cultures, and in finding and developing projects?

You work on Japanese material, but live in the US. What challenges and advantages does your choice of location present, both in “keeping in touch” with both cultures, and in finding and developing projects?

My wife and most of my friends are Japanese, so I still feel very much surrounded by the culture. We speak Japanese at home. My wife works at a Japanese restaurant. It’s very much a little bubble in the greater society. Obviously I don’t have that immersion like when I lived in Japan, but I never feel far away from it. And my translation work keeps me into the language.

The thing I am most out of touch with is pop culture. I don’t know what’s cool anymore, or what the catch phrases are. Fortunately, I specialize in classic manga and Edo period ghost stories so that usually isn’t too much of an issue!

The same thing happened when I lived in Japan. Coming back to the US required me to relearn what had been going on in my native land while I was gone. I’m nostalgic for the times when I had no idea who the Kardashians were or Justin Bieber.

A nostalgia I think we all share! Well, this has been fascinating getting a glimpse into your work and interests. Thank you very much for your time. I’d like to finish up by having you tell us about any other upcoming projects you’re excited about.

I am most excited for the new Kitaro series from Drawn & Quarterly, and Queen Emeraldas from Kodansha. Those are both dream projects for me. Leiji Matsumoto, creator of Queen Emeraldas, is really responsible for me even doing what I do, because seeing his Galaxy Express 999 and Star Blazers (Space Battleship Yamato) years ago completely enamored me of Japanese culture and language. So getting to work on his comics is a huge deal. And Kitaro . . . that’s the reason I got into manga translation.

A good decade ago I stood on a friend’s bar in Osaka and made a drunken vow that I would bring Shigeru Mizuki’s work to English, and finally holding a printed copy of The Birth of Kitaro in my hands feels like a fulfillment of that vow.

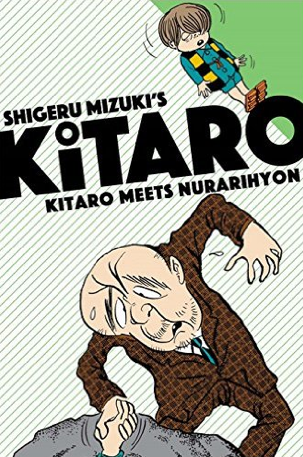

Above: Kitaro meets Nurarihyon, second volume in the Kitaro series, is due out in October 2016.

Alexander O. Smith is translator of thirty novels from the Japanese, including Brave Story and The Book of Heroes by Miyuki Miyabe, The Devotion of Suspect X by Keigo Higashino, and the Guin Saga series by Kaoru Kurimoto. He is also known for localization and production of video games, and is cofounder of publisher Bento Books.